If you want to save for retirement in an account or accounts not linked to your job, you have two choices: Traditional IRAs and Roth IRAs.

If you want to save for retirement in an account or accounts not linked to your job, you have two choices: Traditional IRAs and Roth IRAs.

This article gives you guidance about which type you should choose to contribute to. It focuses on the key distinctions between the two types:

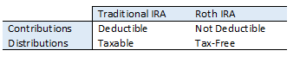

- Contributions to Traditional IRAs are fully tax deductible unless your income is “too high.” For the purposes of this article, we will assume that your income is low enough to allow full deductibility.

- Contributions to Roth IRAs are not tax deductible – they are made with “after-tax” dollars.

- Distributions from Traditional IRAs are fully taxable unless you have made “after-tax” contributions. We will assume that you have not.

- Distributions from Roth IRAs are not taxable.

Both account types offer tax-deferred accumulation. But the US Government requires tax payments in either case. With Roth IRAs, you pay income tax now, and none later. With Traditional IRAs, you pay no income tax now, and full income tax later.

Both types of IRAs are subject to the same contribution limits, which can change every year, and which vary somewhat with the age of the contributor.

This article focuses on the implications of the differences between the IRA types in the income tax treatment of contributions and distributions. It does not address the complexities of the complete rules about IRA contributions and distributions.[1]

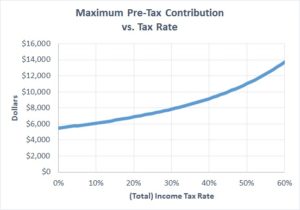

As we start, I’d like to highlight an essential element of fair comparison between Roth and traditional IRAs: it takes more after-tax income to make a maximum contribution to a Roth IRA than to a traditional IRA.[2] It’s not fair to compare the results for $5,500 Traditional IRA and $5,500 Roth IRA contributions – taxes have already been paid on the Roth contribution. As the graph indicates, for higher tax rates, more tax must be paid to leave $5,500 after tax for a Roth IRA contribution. For example, if your tax rate is 30%, your pre-tax contribution for a $5,500 Roth contribution is almost $8,000 ($7,857 to be precise).

With that essential understanding as prologue, let’s move on to our rules.

Since you must pay income tax either now or later, you might think that you should choose the account type that requires you to pay tax at the lower rate. In fact, this is true, and gives rise to

- Simple Rule 1: Choose the account type that allows you to pay taxes at the lower rate.

- If you expect your tax bracket after you retire to be higher than your tax bracket now, pick the Roth (and pay taxes now, in the lower tax bracket).

- As long as your pre-tax contribution is no larger than the maximum.

- If you expect your tax bracket after you retire to be lower than your tax bracket now, pick the Traditional (and pay taxes later, in the lower bracket).

- If you expect your tax bracket after you retire to be higher than your tax bracket now, pick the Roth (and pay taxes now, in the lower tax bracket).

But, what if the tax rates are the same? It turns out that the mathematical formulas for after-tax account values for Traditional IRAs and Roth IRAs are identical if your current and post-retirement tax rates are the same. So, it doesn’t seem to matter which you choose in that case.

However, recall that maximum pre-tax contributions are larger for Roth IRAs than for Traditional IRAs

As we said above, if you are in the 30% tax bracket, it will cost you $7,857 in pre-tax income to make a $5,500 (after-tax) Roth contribution, vs only $5,500 in pre-tax income for the Traditional IRA contribution. So there is more after-tax money in the Roth account, earning tax-deferred returns. This implies

- Simple Rule 2: If you expect your current and post-retirement tax rates to be the same, and if you can afford to make a larger contribution than the pre-tax maximum, make it a Roth contribution.

For a little more intuition on this, suppose that you can afford only to make the pre-tax contribution (currently $5,500). If your tax bracket is 30%, you’d make a $5,500 Traditional IRA contribution or a $3,850 Roth IRA contribution (30% tax on $5,500 is $1,650; subtracting $1,650 from $5,500 leaves $3,850). According to Simple Rule 1, these would both yield the same after-tax distributions after you retire. Now suppose that, on the last day of the year, you get a $2,357 bonus, and you decide to save it all (warming the heart of your favorite financial planner!). If you’ve made a $5,500 Traditional IRA contribution, you have to save the bonus in a taxable account. But, if you’ve made a $3,850 Roth IRA contribution, you have just enough room to save $1,650 (the after-tax income from your $2,357 bonus) into your Roth IRA. Since that money will grow tax-deferred (in fact, tax-free!), this has to be a good idea.

For many people, these simple rules will suffice. Many people want to make less than the maximum contribution to their Traditional IRA, and most people expect their tax bracket to be lower after they retire. Many other people expect their tax bracket to be the same after they retire.

Unfortunately, the world isn’t always simple. As the caveat in Rule 1 suggests, if you want to make a large contribution, larger than the pre-tax maximum, and if you expect a lower tax rate after you retire, more analysis is required. There is a trade-off:

- Using the Traditional IRA allows you to take a tax deduction for your contribution, and using the Roth doesn’t. This tax deduction is more valuable for larger current tax rates and lower post-retirement tax rates.

- Using the Roth allows you to get tax-deferral on more dollars. This extra tax deferral is likely to be more valuable if

- You can use it for a long time (retirement is a long way off)

- You can use if for tax-inefficient investments (like bonds)

Working through the trade-offs turns out to be very complicated. Factors we have to consider include:

- The difference between expected current and post-retirement tax rates

- The time to distribution after retirement

- Whether you intend to invest your savings in stocks or bonds

- The expected interest rate on bonds

- The expected rate of return on stocks

- The composition of the rate of return on stocks (how much dividends, how much capital appreciation)

As you might imagine, capturing all of these factors (and variations in all of these factors) in a single rule is not easy. Nevertheless, here is a simplified version:

- (Not simple) rule 3: If your current tax rate is higher than the rate you expect to pay in retirement, and you wish to contribute more than the pre-tax maximum,

- Choose the Traditional IRA and contribute the excess to a taxable account if:

- Your current tax rate is much higher than you expect to pay after retirement (the tax deduction is likely to be more valuable)

- Tax deferral is likely to be less valuable:

- It’s only a few years until you expect to distribute the contribution

- You expect to invest your savings in tax-efficient vehicles (like stocks)

- Choose the Roth IRA (and contribute any excess to a taxable account) if

- Your current tax rate is close to the rate that you expect to pay after retirement (this is like Rule 2)

- The tax deferral is likely to be more valuable

- It’s many years until you expect to distribute the contribution

- You expect to invest in tax-inefficient investments (like bonds)

- Choose the Traditional IRA and contribute the excess to a taxable account if:

As you might imagine, quantifying Rule 3 turns out to be impossible (it’s an algebraic equation). If you are uncertain, ask your advisor to help you.

Summarizing the contribution rules:

| Post-retirement tax rate relative to current tax rate | ||||

| Lower | Higher | The same | ||

| Size of pre-tax contribution relative to maximum | Smaller | Traditional | Roth | Roth[3] |

| Larger | See Rule 3 (it’s complicated) | Roth | Roth | |

[1] For example, maximum contributions, how maximum contributions vary by age, contribution deductibility for income tax purposes, tax penalties for early withdrawals, etc.

[2] For example, if current and post-retirement tax rates are both 25%, it takes $7,333 in pre-tax income to make a $5,500 Roth contribution – 25% tax on $7,333 is $1,833, leaving exactly $5,500 to contribute.

[3] Purely from the perspective of the value of after-tax distribution amounts, you could choose either Traditional or Roth, as Rule 2 indicates. However, advantages in minimum distributions and inheritance make the Roth more attractive.