In this installment of my series on employee benefits, I will cover employee stock purchase plans (ESPPs), which offer the ability to purchase employer stock through payroll deductions. Only about 30% of eligible participants take advantage of these plans, and on average, those who don’t participate miss out on over $3,000 per year[1]. You might be asking “Why should I consider this type of plan?” since Sensible Financial doesn’t recommend holding individual stock, especially employer stock. The answer – you can receive a risk-free 17.6% or more rate of return on your contributions so long as you sell the shares immediately upon receipt. Keep reading to find out how these plans work and why we think you should maximize your contributions to the ESPP, cash flow allowing.

What is an Employee Stock Purchase Plan (ESPP)?

ESPPs are generally offered by publicly traded companies and allow employees the option to purchase company stock through after-tax payroll deductions. ESPPs can come in many varieties, but I’m going to focus on the most common type of plan that offers a discount and a “lookback period” (more on these in a minute). ESPPs have an offering period (generally 6 months in length), stretching between the start and end date between which payroll contributions accumulate. Before the offering period begins, you authorize payroll deductions as a percentage of your salary. At the end of the offering period, your accumulated contributions purchase company stock. The two most valuable features of an ESPP are that your company may offer shares at up to a 15% discount and can also offer what’s called a “lookback period”. A plan that offers a lookback compares the stock price at the beginning and end of the offering period and any discount is based on the lower of the two prices. ESPPs generally have a maximum annual purchase limit of $25,000. The ESPP contribution limit is determined by the pre-discount price. If you assume no movement in the stock price between the beginning and ending of the offering period, and you receive a 15% discount, you can contribute only $21,250 (85% of $25,000) to the plan in a calendar year period.

Let’s look at a few examples:

- Suppose the offering period is January 1 – June 30th. On January 1 the stock price is $100 and on June 30th the stock price is $110. If your company offers a 15% discount and a lookback, you will receive shares on June 30th (end of the offering period) for $85 that are worth $110. [Lower of the two prices is $100, and you get a 15% discount and pay $85; stock is worth $110 at the end of the period.]

- But what happens if the stock price goes down during the offering period? Well, let’s just flip the share price so that it is $110 at the beginning of the offering period and $100 at the end. In this case, you still purchase shares for $85 but they are worth $100.

Benefits

With a plan that offers a discount and lookback period, the biggest benefits you receive are a 15% discount on your shares plus the upside of any price increase during the offering period. Many plans also allow you the option to back out of the plan prior to the end of the offering period. If you had this option and an emergency arose, your accumulated contributions would be returned to you. After your employer retirement plan match, ESPP discounts are the second-best option for no-risk savings. It even makes sense to borrow to fully participate in your ESPP if the interest rate is lower than your expected return.

Risks

You might be wondering, what’s the risk here? We recommend selling immediately at the end of the offering period when your profit is risk-free. That said, many people hold onto their shares beyond the end of the offering period. Some plans impose limits on when you can sell your shares. Holding the shares beyond the end of the offering period poses the risk that the shares lose value. You are not compensated for taking this risk.

Tax treatment

With ESPPs, you pay no tax until you sell your shares. This is an important distinction relative to most other equity compensation plans. Nor will you have to deal with alternative minimum tax (AMT).

The tax treatment on the sale of ESPP shares depends on whether you satisfy a special holding period, defined as the later of:

- Two years after the date the company granted the option (generally, the start of the offering period);

- One year after the date you received the stock (generally, the end of the offering period when you purchase the shares with your accumulated contributions).

Your employer will provide you (and the IRS) a form 3922 which will detail all the important dates and prices needed to calculate the tax. This will help you (or your accountant) properly calculate any tax liability you owe.

Disqualifying Disposition

If you sell the shares before meeting the special holding period (outlined above), you are deemed to have made a disqualifying disposition. The tax treatment of your sale under this circumstance is easy to calculate. Any discount you receive on the shares is treated as compensation income. Your basis is the purchase price of the shares plus any compensation income. If you sell the shares after the end of the holding period, the updated basis is subtracted from your sale price to determine your capital gain.

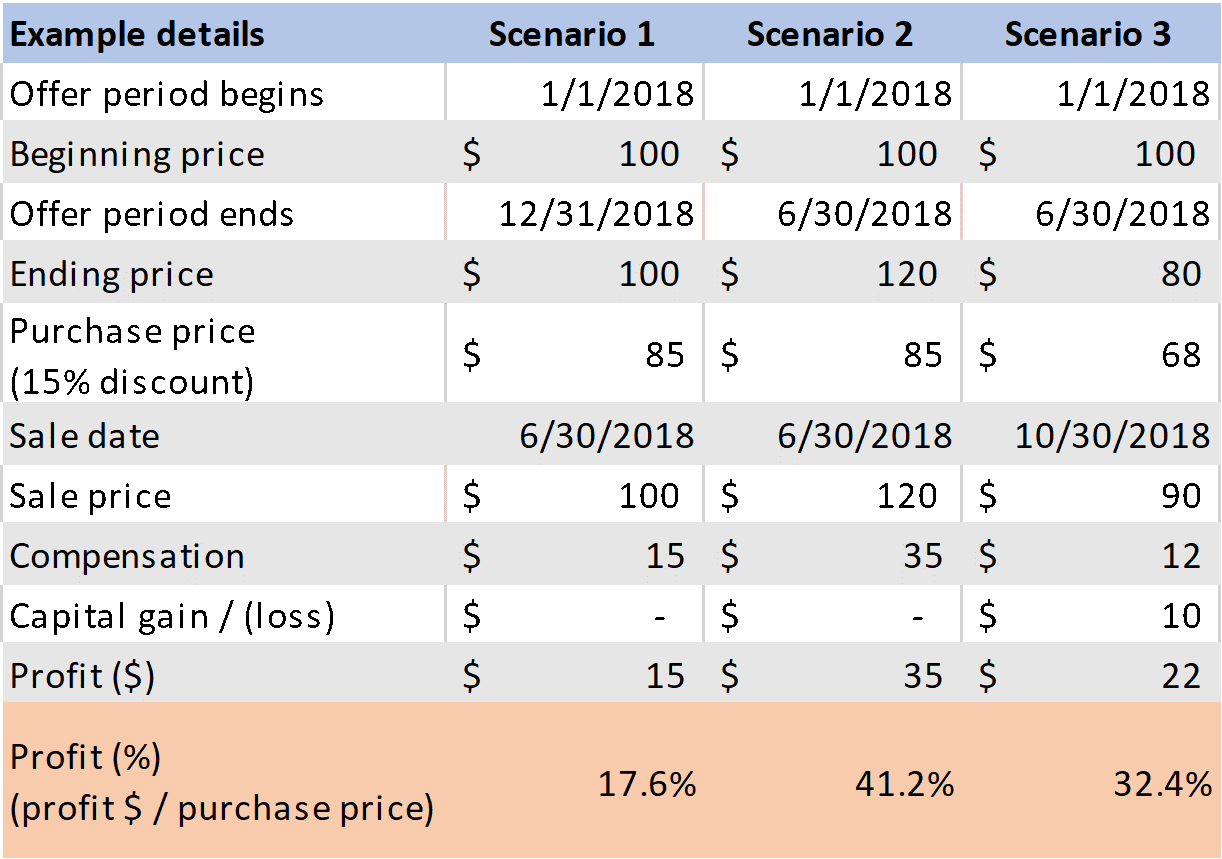

Let’s look at a few examples of a disqualifying disposition:

- Scenario 1. The shares are worth $100 at the beginning and end of the offering period. You purchase the shares at a 15% discount for $85 and sell them at the end of the offering period for $100. You received a $15 profit on your original purchase price of $85. This translates to the minimum 17.6% profit mentioned earlier. For tax purposes, this gain is treated as compensation income.

- Scenario 2. The shares are worth $100 at the beginning of the offering period and $120 at the end. You purchase the shares at a 15% discount on the lower of the beginning or ending offering period prices. You sell the shares at the end of the offering period for $120, making a $35 profit ($120 sale price minus $85 purchase price).

- Scenario 3.The shares are worth $100 at the beginning of the offering period and $80 at the end. You receive a 15% discount and purchase the shares for $68. You hold the shares for three months after the offering period ends and sell them for $90. The discount you received on the shares is $12, taxed as compensation income. The sale price of $90 minus your basis of $80 (purchase price of $68 plus compensation income of $12) gives you a short-term capital gain of $10.

Qualifying Disposition

If you plan to sell your ESPP shares at the end of the offering period (recommended), you can skip the remainder of this tax section.

With a qualifying disposition, you held your shares for at least two years from the beginning of the offering period and at least one year from when you received the shares. At the time of sale, there is still a portion that is taxed as compensation income and a portion taxed as capital gain. Compensation income is calculated differently with a qualifying disposition than with a disqualifying disposition. In this case, the compensation income is the lower of:

- The per-share profit

- The difference between the grant price of the share (beginning of offering period) and the option price of the share (price you receive the shares for at the end of the offering period).

The difference between the grant price of the share (beginning of offering period) and the option price of the share (price you receive the shares for at the end of the offering period).

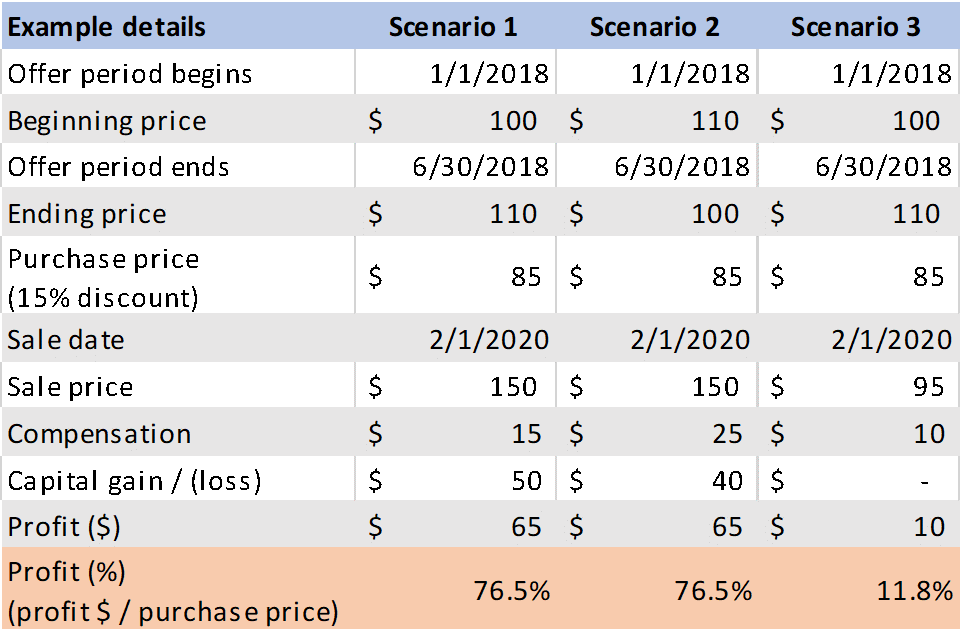

Let’s look at few examples of a qualifying disposition:

- Scenario 1. The shares are worth $100 at the beginning of the offering period and $110 at the end. You hold them long enough for a qualifying disposition and sell them two years later when they are worth $150. In this case, you received the shares for $85 and they were worth $100 when they were granted (beginning of the offering period). You have $15 in compensation income and $50 in long-term capital gains (difference between $150 sale price and your updated basis of $100).

- Scenario 2. The shares are worth $110 at the beginning of the offering period and only $100 at the end. You sell for $150 in a qualifying disposition. In this case, the compensation income is $25 (difference between $110 beginning price and $85 purchase price) and the long-term capital gain is $40. We see that if the share price decreases during the offering window, your total gain remains the same, but the compensation portion of the gain is larger. In this case, you’d be better off from a tax perspective by selling the shares in a disqualifying disposition. In a disqualifying disposition, the compensation income would only be $15 and the long-term gain would be $50.

- Scenario 3. In this final example, let’s assume the price is $100 at the beginning of the offering period and $110 at the end. You hold the shares for two years and then decide to sell them after they declined in value to $95. Can you guess what the compensation income is? If you answered $10, you are correct. Your basis increases to $95 (purchase price of $85 plus $10 in compensation income realized) so no capital gains are realized when you sell for $95.

Conclusion

It pays to understand and take advantage of every valuable benefit your employer offers. ESPPs offer a very low to no-risk opportunity with significant upside. Selling the shares when you receive them limits your risk while you receive the discount your employer offers and any offering period stock price appreciation. With the plans described in the article, the minimum profit is 17.6% if you sell immediately upon receiving the shares. This benefit translates to at least an additional $3,740[1] each year if you maximize your contributions.

The details of your ESPP may differ from the examples discussed in this article. You may also have questions about where to prioritize your savings dollars. If you have any questions about how your ESPP works or whether and how much to participate, please contact your advisor for guidance.

[1] Babenko, Ilona and Sen, Rik, Money Left on the Table: An Analysis of Participation in Employee Stock Purchase Plans (March 14, 2014). Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 27, pp. 3658-3698, 2014. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2166012

[2] $21,250 contribution limit (based on a 15% discount on $25,000) multiplied by a minimum of 17.6% profit.