The government has no resources of its own. When the government spends, it uses resources

- Acquired from taxpayers by taxation; or

- Borrowed from bond purchasers.

Thus, the arithmetic of government finance is simple: spending must equal tax receipts plus new borrowing. Any excess of spending over tax receipts is called the deficit. The national debt equals the cumulative history of deficits.

If the government prints more money, will that cause inflation?

The US Treasury can indeed print money, and Federal Reserve Banks (“the Fed”) can create bank reserves, a form of money that banks hold in their accounts at the Fed. However, neither the Treasury nor the Fed buys goods and services directly with “newly minted” money.

Instead, the Fed puts “new” money into circulation in one of two ways:

- It buys assets. Specifically, the Fed buys Treasury bonds from commercial banks with the newly created reserves. The amount of bank assets doesn’t change, but their composition does. When bank holdings of Treasury bonds fall, their reserves (account balances at the Fed) rise by the same amount.

- It trades cash to banks in exchange for reserves. When banks want more cash, they pay for that cash with reserves. Again, bank asset amounts haven’t changed, but the composition of bank assets has. When bank reserves decrease, bank cash increases by the same amount.

Thus, issuing money doesn’t change the amount of government debt held outside the Fed, it just changes its composition. Cash or bank reserves (which are both government debt) rise for banks, but their Treasury Bonds (another kind of government debt) drop by the same amount.

Now, neither issuing bonds nor issuing money is necessarily bad.

In fact, as economists are fond of observing, both money and government bonds provide valuable services. People use money to facilitate transactions, to store savings, and to keep track of their financial progress. Government bonds also serve to store savings and to provide (currently, at least) low-risk investment opportunities.

Deficit spending gives rise to three primary concerns:

- Transparency: Deficits break the link between taxing and spending. When our government limits its spending to tax receipts, the Congress must gain the assent of the citizenry when deciding how and how much to spend. When the government finances spending with deficits, it is much less clear who is paying how much. It can appear that the resources are “free.” The governing party can literally buy votes by undertaking projects the broader citizenry might oppose if they knew the true costs.

- Wasteful spending: While the ideal economic model of deficit spending envisions a dispassionate decision-maker carefully identifying economic growth-enhancing projects, recent experience illustrates that legislative reality is far different. Republicans and Democrats wanted to help their (somewhat different) constituencies with pandemic “stimulus.” As the old saw says, “you don’t want to watch the sausage being made.”

- Surplus bonds and/or money: While people value the services bonds and money provide, their demands for those services are not unlimited. When people have more of anything than they want or need, they tend to sell that something. When many people are selling, prices fall. A falling price for bonds implies rising interest rates. A falling price of money is inflation. Thus, we’ve identified the providers of deficit spending resources – anyone who holds depreciating bonds or currency.

What does history tell us?

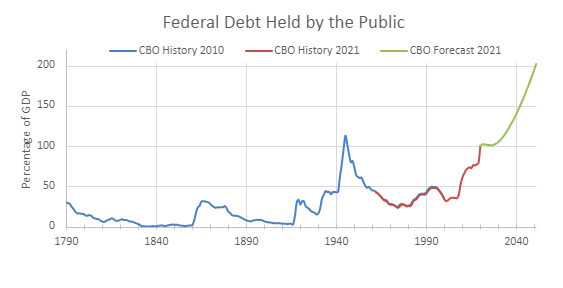

Historically, the United States has run large deficits only in times of severe national emergency. The chart shows the history of the national debt relative to GDP (the size of the economy) since 1790. (The Constitution was ratified in 1788, and as anyone who has seen the musical Hamilton knows, the Federal Government assumed state debts in 1790 under the leadership of Alexander Hamilton.) The US borrowed heavily for major wars and the Great Depression, then paid down the debt or allowed it to shrink relative to the economy after the emergency passed.

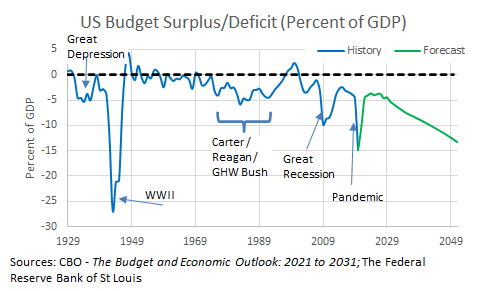

The CBO (Congressional Budget Office) forecasts that the Federal Debt will grow dramatically if current Federal tax law and expenditure plans continue unaltered. Deficits (chart below) after World War II were under 3% of GDP from 1947 through 1974. This covers the Korean War, the construction of the interstate highway system, the Viet Nam War, and the NASA projects culminating in the moon landing.

This changed in the late 1970s during the Carter, Reagan, and GHW Bush presidencies and their associated Congresses. All three administrations ran relatively large deficits, even though none faced a major emergency such as the ones highlighted above.

During the Clinton and GW Bush presidencies, the trend toward large deficits reversed. There were even surpluses in some years. Since the Great Recession, however, the deficits have returned on a grander scale. The Congressional Budget Office now forecasts large deficits far into the future, and an associated growth in the national debt.

Should we worry about imminent inflation?

We saw neither an acceleration of inflation nor rising interest rates after the Great Recession, and we are not seeing rising interest rates now. The Federal Reserve believes the current episode of higher inflation is only temporary, even though our deficits and our debt are larger than they have been throughout most of the country’s history. Doesn’t recent history indicate that we don’t have to worry?

Economists of all stripes agree “too much” borrowing and money creation can lead to rising interest rates and higher inflation. They don’t agree on how and why, nor do they agree on how much is “too much.” These disagreements date at least from the early 20th century with John Maynard Keynes, a forceful advocate of deficit spending to counter shortfalls in aggregate demand during times of recession.

The disagreements revolve around the causes of business cycles, the value created by government spending, and the extent to which government borrowing competes with private investment.

The disagreements remain unresolved. Economists have yet to develop consensus around a theory to explain the business cycles, worldwide monetary and fiscal policies, and interest rate and inflation paths the countries of the world have experienced.

The world is in flux, complicating the macroeconomic problem

- A very large portion of US currency and US Treasury debt is held outside the US. It is enormously difficult to predict how inflation will progress when many holders of cash are using it for purposes that are at best opaque and may have little relationship to economic activity in the US. It is equally difficult to predict how interest rates on US Treasury bonds will develop when large fractions are held by foreign governments. The relationship of the quantity of US currency and US government debt to US economic activity is weaker than it would be if both were used only in the domestic economy. The US Dollar is the world’s reserve currency – its value is also influenced by innumerable non-US factors.

- Consumers and companies use money very differently than they used to:

- Electronic payments have become increasingly important. They are less costly than checks or cash and take less time. I suspect consumers can manage with less cash and smaller checking accounts. I carry less physical cash and replenish my wallet much less frequently than I used to. I’m confident this affects the relationship between the quantity of money and inflation. I’m also confident that no one knows how.

- The advent and growth of online banking also changes the relationship between various types of accounts and economic activity. It is much easier to move funds between checking accounts and savings accounts than it used to be. People can hold more in savings and less in checking, on average. Especially as interest rates rise, this will change the relationship between account balances of various types and economic activity.

Taken together, these considerations make it difficult to predict how much the US government can borrow and how much of that borrowing it can “monetize” (how much money the Fed can issue in exchange for Treasury bonds) without generating higher interest rates, higher inflation, or both.

There are two additional concerns:

- Deficit spending exacerbates the risk of government misallocation of resources. For example, during the Great Recession, the Congress authorized bailouts for insolvent bankers who received bonuses into the bargain. Almost no one (other than the bankers) was happy about that.

- Larger government debt risks hamstringing the government’s ability to spend. As interest rates rise, government interest payments take up a larger portion of the Federal budget. Here is the simple math:

- In 2021, the debt is about 100% of GDP (gross domestic product), and the average interest rate on Federal borrowing is roughly 2%. Interest payments are about 2% of GDP. The Federal budget is (very) roughly 24% of GDP. Interest payments are thus 2%/24% = about 8.3% of the budget.

- Suppose the debt doubles as a percentage of GDP to 200% (as the CBO forecasts by 2051), and interest rates rise to 5%. Interest payments would be 10% (5% times 200%) of GDP, or roughly 40% of the budget (10%/24%) if its share of GDP doesn’t change. That would place a straitjacket on government spending. If a true emergency were then to occur, the government might try to respond, but its promise to pay interest and repay principal would not be credible. A very serious financial crisis would likely ensue.

- (Imagine that you’ve just stretched to buy a house with a 30-year mortgage with an adjustable interest rate. You’ve carefully budgeted, and if everything goes right, you’ll be able to manage. Then the bank calls with the news that the interest rate has doubled from 3% to 6%. You are in big trouble!).

Expanding deficit spending increases the debt while funding projects that taxpayers may not support. Growing debt threatens the credibility of the government’s ability to meet its obligations, and consequently threatens to weaken the value of its promises – Treasury bonds and US currency.

Are significantly higher inflation and higher interest rates coming? Probably not. Is there more risk of higher inflation and higher interest rates than there would have been without the deficit spending-funded pandemic support and now infrastructure? Yes, there is. Does the risk of inflation and higher interest rates grow if deficits and the debt continue to grow as shares of GDP? Yes, it does.

Taxpayers, bond holders, and holders of currency (that means all of us) will want to pay close attention to the actions of the federal government. Ongoing deficits in non-emergency situations would be concerning. Growing the debt relative to GDP would be concerning.

On the other hand, reducing deficits and a declining ratio of debt to GDP would be encouraging.

We will have to wait and see.

This article originally appeared in Forbes.com.

Photo by Pepi Stojanovski on Unsplash